Nestled among brown high rises on the Upper West Side, the sleek, mostly glass Calhoun School stands out in more than one way. The completely windowed building invites New York City into the classroom, and in return the school utilizes the city as part of the students’ progressive learning process. Whether exploring an organic farm for a food politics class (taught by their head chef, Chef Bobo, from the French Culinary Institute), taking trips to the Natural Museum of History for biology, or just stepping into Central Park while reading Catcher in the Rye, Calhoun strives to incorporate real world issues into the classroom with a very unconventional scheduling approach.

The Calhoun School is one example of the type of schools Westminster has been visiting while re-evaluating its own schedule. Using the strategic plan as a compass, Westminster has been trying to reassess its current schedule. The Time Task Force, a varied group of teachers focused on building a proposal for a new schedule, decided to explore schools across the country that have unique schedules or have recently undergone a drastic schedule change to gather information necessary to make a well-informed proposal. Furthermore, the Task Force invited students to come on these trips to gather other students’ perspectives and to encourage student input on our own schedule.

The Task Force’s first trip was to New York to look at Calhoun, a school in the city, and Montclair Kimberly Academy, a school in New Jersey. The team included teacher, coach, and parent Ellen Vesey, coach and new teacher Akwetee Watkins, and assistant principal and group leader Jim Justice as well as student representatives. Sophomore Ruwenne Moodley, junior Jack Bondurant, and I represented the student body. Our job was to understand students’ honest reactions to their schedules and evaluate why parts of these schedules could work or not work at Westminster.

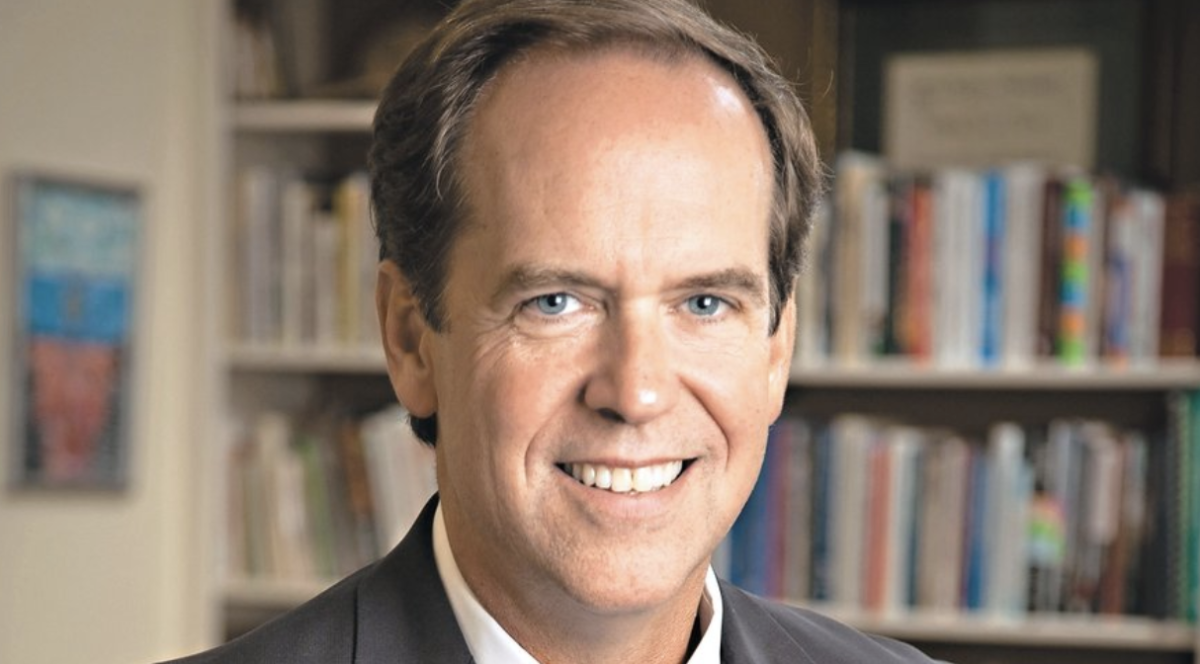

Our first destination was Montclair Kimberly Academy, or MKA, in Montclair, New Jersey. After being mistaken for students out of dress code, we were told to wait in the visitors’ room for more instructions. I was wary of the prospect of spending a day wandering around a school intrusively asking questions, so I was relieved when Dr. David Flocco, the head of campus and man in charge of the schedule change, walked in and handed us each a schedule to follow. Flocco had a quick discussion with us about the preliminary reasons for MKA’s schedule change, which were initiated by Flocco in response to his doctoral research on school schedules relating to student stress. After this introductory meeting, Ruwenne, Jack, and I were each introduced to a student to shadow while the teachers were told to roam freely.

My first class was a freshman civilizations course led by teacher Carol Spencer. Spencer allowed time for class discussion about their reactions to the schedule since the freshmen had never experienced a block schedule with 75-minute periods. Students said the extended periods prevented them from “constantly looking at the clock” and allowed them to “cover more material and learn so much more.”

Spencer, who has been a teacher for 23 years and was at MKA during the schedule change, is known around school for always having engaging classes, probably due to her background.

“I was really used to hands-on teaching from after the whole hippie movement when education became much less rigid and much more, ‘How do you feel?’” said Spencer, “so switching schedules was pretty easy for me.”

For some teachers, however, the switch might not have been as easy. I asked a group of freshmen girls if there were any classes or teachers that they dread and they all responded instantaneously, “Mr. Bink,” known for leading predominantly lecture-oriented classes. Moments later, I walked into my second-period biology class, and the teacher introduced himself to me as Mr. Bink.

“I have experience teaching college courses anywhere from 50 minutes to three hours” said Bink, “so adjusting to 75 minutes was not too difficult.”

In Flocco’s doctoral research, he argues that the schedule change has led to “reduced student stress, increased faculty engagement, and significant academic gains for students.” While Spencer agrees that longer class periods have taken some pressure off of teachers, she’s skeptical how much it has helped her students.

“I’ll be honest, the culture of the school is very competitive. A lot is expected of the students by their parents and the goal is hopefully Ivy League, or the top tier schools,” said Spencer. “The freshmen now are maybe in a little bit of a honeymoon period, but they’re going to be finding that there’s going to be a lot on their plates, and they’re going to be stressed.”

In Advanced Biology and AP English Language, the upperclassmen seemed to have discovered the stress the freshmen had not yet encountered. Overall, MKA has a very similar atmosphere to Westminster (with the exception that when my shadow introduced me to some of her peers, she introduced one as “her only conservative friend”), and Flocco’s research argues that the schedule change has been a raging success.

The next day we visited the Calhoun School on the Upper West Side. Not only was the building almost completely glass, students travelled between classes on elevators and sat in classrooms with no walls. I couldn’t believe that such a progressive school had a schedule similar to ours (seven classes per day, 45-minute classes) just three years ago. However, their schedule drastically changed from a two-semester, more traditional schedule to five six-week modules, or “mods,” with two or three 55-minute periods and one two-hour period.

I first sat in on a US history class, which seemed very similar to my own history class with two exceptions: my teacher went by “Jason,” and there was a Spanish class seated about 30 feet to our right and a food politics class on the other side of a bookshelf, creating a much noisier atmosphere than I’m accustomed to. After a club period in which everyone seemed to actually be participating in a club, I warily walked into a two-hour English class. After I briefly introduced myself and explained why I was there, the teacher opened the class up for a discussion about the schedule.

The first girl to speak said that she “hated mods” and that students “can’t be accurately assessed in just six weeks.” Others loved that if they didn’t like their teacher they only had to deal with them for a short period of time. They all agreed that the biggest advantage of the mod system is the number of electives they were allowed to take – they were in shock that I couldn’t take a language class senior year due to our schedule restrictions. Surprisingly, they also raved about the two-hour class period and how it gave them opportunities to go on field trips and have really thorough discussions.

Everything about Calhoun is centered around the student. The lack of APs allows students to set a comfortable pace for themselves, and the constantly changing schedule prevents students from getting caught in a monotonous cycle. I never expected such a seemingly complex and progressive schedule to fit a school so well, and I think Westminster should learn from Calhoun that a drastic change should be approached with enthusiasm, not skepticism.

In addition to the trip to New York, the Time Task Force has taken other students on similar trips to visit the Latin School of Chicago (Oct. 23) and the Hawken School in Ohio (Oct. 29), other schools with unique approaches to learning through their schedules. After the visits are completed, all of the students involved will meet with the Task Force Nov. 7 to discuss their experiences and findings at each school. Once the Task Force has accumulated all of the reactions to these schools’ schedules, they will “go dark,” meaning they will begin to form the proposal for a new schedule to be put in place for the 2013-14 school year.

After almost a decade of talking about the need for a schedule change, the school has committed to making the transformation.

“Our new schedule should be flexible enough to allow for it to develop and evolve as new needs and opportunities arise,” said high school principal Ross Peters.

The schedule change is not anticipated to be a jump to perfection but as an adjustable starting point to create an atmosphere geared to enhance both student performance and student life.

Check out the Time Task Force’s New York trip in action!