The familiar cry of “no taxation without representation” rings a bell from history books, but in 2025, it finds new relevance. On April 2, a day he coined “Liberation Day,” President Donald Trump signed an executive order imposing tariffs on all imported goods. The move surprised financial markets, triggering one of the worst two-day stock market downturns in history. The losses surpassed even those experienced during the 2008 financial crisis and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Remarkably, this crash also outpaced the net losses seen during the early of the Great Depression and Black Monday, the single worst day in stock market history.

Trump invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to justify the tariffs, citing the ongoing issues of illegal immigration and the influx of fentanyl and other drugs into the U.S. The executive order targets countries including Canada, Mexico, China, and others, aiming to hold them accountable for what the administration frames as public health and national security threats. Amid rising tensions with China, the policy could have far-reaching economic and geopolitical implications.

Historically, tariffs were a primary source of federal revenue before the introduction of the income tax. Today, they are largely used as trade policy tools to encourage domestic production, leverage negotiations, and reduce dependency on international markets. However, tariffs come with significant risks. When tariffs placed on goods from countries such as China cause sharp price increases, the costs are often passed directly to American consumers, impacting consumers rather than benefiting domestic industry.

The United States’ incomplete supply chain further complicates the tariffs’ effects. For instance, taxing an imported teacup may promote domestic manufacturing, but if the porcelain required to produce the teacup is still imported, the added cost will ultimately be borne by customers. These rising prices, combined with supply-chain disruptions, threaten to stall economic growth, projected to nearly flatline in 2025.

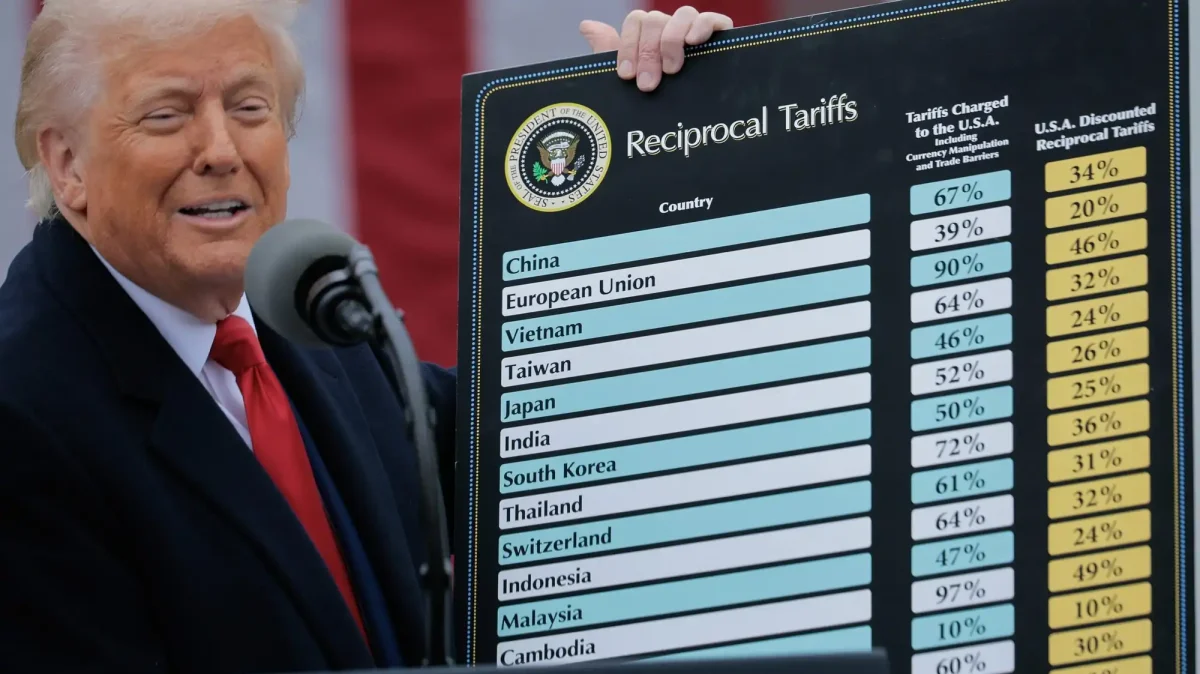

In some cases, Trump’s new policy increases the total tax on imported goods more than tenfold. Where previous tariffs ranged from 2-6%, the new measures raise that to between 22.5-27%. Unlike earlier policies that targeted specific nations or product industries, the latest tariffs include a 10% universal baseline tax on all imports, with additional retaliatory tariffs aimed at countries like China and India—nations that impose steep duties on American goods. Policymakers argue that these policies address global trade injustices, promote American manufacturing, and stimulate economic growth.

Still, the impact of these tariffs is felt on multiple levels. Domestically, producers benefit from reduced foreign competition and the ability to raise prices. The federal government sees a revenue boost from the increased duties. However, consumers face higher prices across domestically produced goods, eroding purchasing power and deepening economic inequality.

Globally, the tariffs are altering international bonds and trade rivalries. For example, exemptions for Taiwan and their semiconductor industry have strengthened U.S-Taiwan ties. Conversely, tariffs on Chinese imports have sparked retaliation, escalating trade tensions.

Politically, the tariffs are a hallmark of the Trump administration and may influence his party’s results in future elections, as this new wave of economic uncertainty has weighed on the president’s approval rating. Recent polls show that 53% of Americans view Trump unfavorably, while only 41% hold a favorable opinion. As inflation rises and investor confidence wanes, the long-term effects of these tariff policies remain highly uncertain, casting a shadow over both the economy and the administration’s political future.

Edited by Sara Dixon