The United States has stepped back from a global effort to combat disinformation, ending agreements with more than 20 countries that were designed to counter false narratives from Russia, China, and Iran. The move dismantles the State Department’s Global Engagement Center, once a hub for coordinating international responses to propaganda and online manipulation. Supporters of the decision argue it protects free speech, while critics warn it leaves students and citizens more vulnerable to the growing power of misinformation, especially as artificial intelligence makes it harder to tell fact from fiction.

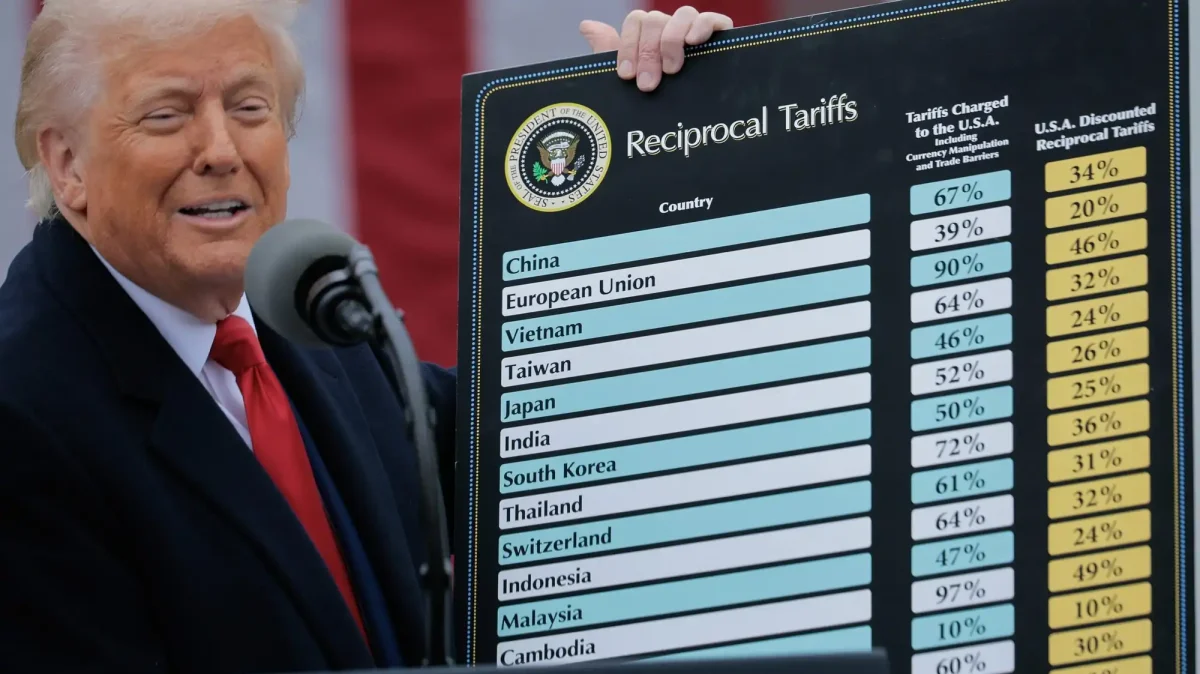

The Global Engagement Center (GEC), originally created in 2011, was a State Department agency that tackled disinformation spread overseas by U.S. adversaries and terror groups, according to the Financial Times. During the Biden administration, the U.S. made formal agreements (called memoranda of understanding, or MOUs) with 22 countries in Europe and Africa. These agreements were meant to create a coordinated approach to identify, track, and respond to disinformation spread by foreign governments, like Russia, China, and Iran. Earlier in 2025, the Trump administration dismantled agencies across the government and terminated these agreements, calling them ineffective as they misaligned with free speech values.

False information has long circulated on social media. While most of the blame typically goes to the users involved, the underlying problem goes back to the platforms. Yale Insights, the online publication of Yale School of Management, found that the social media reward system (likes, comments, and shares) directly promotes misinformation online. Users who post for engagement were far more responsible for the false headlines shared. Users shared misinformation mainly for engagement, not ideology. The deep underlying issue is that platforms incentivize attention over accuracy, not that users are lazy or don’t care about the truth.

Although the reward system for platforms has been found to be broken, there have been efforts to combat such misinformation. During recent years, social media platform X has introduced community notes, a crowdsourced fact-checking system. Users are able to add notes to misleading information and provide more context.

“I think they’ve [X] made very good bounds, because they don’t censor the tweets, but they have a box under the tweets that gives factual information or context,” said sophomore Ved Nooka.

Supporters argue this system reduces misinformation while preserving users’ voices. With the US stepping back on its efforts, the responsibility lies more on the platforms themselves to combat misinformation.

As more young people join social media, many are turning to TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram for news, leaving them more vulnerable to false information than ever. As the government steps back, the burden shifts to young people to stay vigilant on social media and distinguish fact from falsehood. It does beg the question of if students should be more readily prepared to fact-check and actively combat misinformation.

“I think they [schools] could really go more in-depth on combating misinformation,” said Nooka. “We’ve been taught to cite our sources since middle school, which is good, but they could go more in-depth for specific classes when you are researching and finding information.”

Schools have implemented research projects to teach students to cite sources, but am looking to now incorporate more curriculum on how students can find credible sources in news. Others argue that schools already provide sufficient training, and that the deeper challenges of online disinformation are beyond what classrooms can realistically address.

“I would say that schools don’t really change,” said history teacher David Abraham. “If you want to find out what’s true, you have to be aware that there are people who have interests in infecting your mind one way or another, and it’s always going to be an uphill battle.”

Edited by Lilya Elchahal