With a quick glance up, the athlete saw an open passing lane to his left. Dribbling at speed toward the defender, with a stepover and head fake, he feigned a right pass with the intent of sending the ball directly in between the opposing defenders. However, as he planted his right foot, an incredible pain soared through his leg and there was a loud pop. He fell to the ground, grimacing and grabbing his knee. Players, trainers, and fans standing on the sideline winced at the probable injury—an ACL tear.

Horrifying stories of one of sports’ most threatening injuries have been more common than usual among Westminster athletes this year. Seniors Isabelle Tehrani and Parker Tuthill, along with sophomore Sheridan Nulty, have spent much of the fall limping around campus on crutches. A football captain and running back, Tuthill was injured early in the season in a game against Providence.

“I was going up the right side and tried to cut left because I saw a seam,” he said. “I planted and felt a pop. It was a really shocking feeling. I had no idea what happened.”

At first, the trainers thought Tuthill’s knee was just dislocated, a common initial diagnosis when dealing with ACL tears.

Tehrani’s injury occurred at a basketball exposure camp, where she hoped to get scouted by colleges.

“There was a loud popping noise coupled with the worst pain I’ve ever felt in my life,” she said.

Nulty was playing in a club soccer game. “I was dribbling to the right and then decided to cut back to the left,” she said. “I cut too sharply and felt my leg twist.”

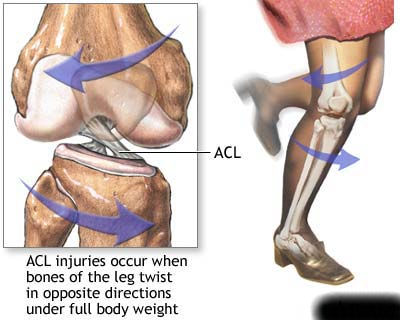

The anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, is one of the four main ligaments that connect the femur to the tibia. It plays a major role in providing rotational stability for the knee, and without it, athletes are useless.

Medical officials estimate approximately 200,000 ACL tears occur each year. Female athletes are even more likely to suffer from this injury than males, due to the combination of wider hips and lower muscle percentage. Furthermore, females have a higher range of flexibility, which means their muscles and ligaments are more lax.

“Another reason,” added head athletic trainer, Donna Hays, “is that females have a more uneven strength balance between their hamstring and quadriceps muscle than males.”

Just after injury, trainers or doctors perform a knee assessment.

“A lot of times I have an idea of what has happened before I even do an evaluation, based on the athlete’s history and the injury scenario,” explains Hays. There is no way, however, to be completely sure until an MRI is performed. An MRI also shows any other damage to the knee.

“The trainers knew immediately it was my ACL,” Tuthill said. “They didn’t know I had also torn my meniscus until the MRI results came back.”

Surgery is required to reconstruct a new ACL. Prior to surgery, however, the athlete must begin “prehabilitation” in order to maintain muscle strength and range of motion, as well as to reduce swelling. This includes riding the stationary bike without resistance, leg stretches and extensions, squats and other muscle-building exercises, as well as icing and compression.

After prehabilitation, the knee begins to feel normal, and eager athletes often hope this means they can return to running, cutting, and jumping. In reality, this will cause further injury to the knee and only prolong the recovery time after surgery. Nulty has been undergoing prehab for over a month, as her surgery was postponed due to cuts on her knee that could increase the risk of infection.

Years ago, ACL tears used to be a career-ending injury for many athletes. Now, however, because of the frequency with which these injuries occur, orthopedists and physical therapists have become very experienced in helping the athlete return fully. When the ACL is torn, it eventually disintegrates inside the knee. The surgeon, therefore, must construct a new ACL. Typically doctors use a portion of the athlete’s patella tendon or that of a cadaver.

“The patella tendon is the most durable,” said Hays, “but can have differing effects down the road.” For Tehrani, however, the doctor opted to use part of her quadriceps muscle to create a new ACL.

“My surgeon, [Dr. Xerogeanes]wanted to use my quad muscle,” said Tehrani, “because it leads to a lot less scarring.”

Dr. Xerogeanes, known by his patients as Dr. X, is a leading orthopedic surgeon who does many of the surgeries for Emory and Georgia Tech athletes, as well as for many celebrities, including actor Matthew McConaughey.

“Dr. X is going to decide in the middle of surgery whether or not to use my patella tendon or my quad,” said Nulty, “based on what everything looks like once he opens my knee up.”

For Tuthill, Westminster parent and orthopedist Dr. Jon York used the patella tendon.

Hays explained reconstruction surgery using a piece of string cheese.

“Think of the patella tendon as a piece of string cheese. The doctor peels a piece off of the patella tendon with bone pieces on either end. He then attaches screws into each end of the bone. Using a drill, the doctor threads the tendon up through the lower knee and screws the bone in, creating a new ACL out of the patella tendon. The missing piece of the patella tendon will eventually regrow.”

Depending on the athlete, complete recovery after surgery takes between six months to a year.

“Rehab is like a recipe,” said Hays. “Just like you have to alter ingredients based on your tastes, you have to develop specific rehab programs based on the athletes’ recovery speeds.”

This period is important not only to regain stability and strength but also to prevent a second tear in the future.

“We see this especially in girls,” Hays notes, “When they are finally able to return to sports, they either re-tear the same ACL or tear the other one.”

For the first three months that follow surgery, athletes must be extremely diligent in their recovery. The first three weeks include icing multiple times a day and learning to walk without crutches. Following this initial 12-week period, athletes spend three to five months in strength and agility training, working with a physical therapist on weight machines, planting and cutting drills, and cardiovascular workouts. An important component of rehab is balance exercises.

It is important that the athlete is not overly aggressive during rehab, because although the knee might feel stable, an integral part of recovery is waiting for the bone plugs to heal.

As athletes become more competitive in sports each year, the risk for ACL tears and other serious injuries increases.

Like many other schools and sports programs, Westminter coaches and trainers have begun workouts in hopes of preventing ACL tears. This includes agility ladders, jumping hurdles, and strength exercises, as well as stretching.

Despite the frustration and heartbreak of their injuries, Nulty, Tehrani, and Tuthill have kept positive attitudes as they head into the long road to recovery.